Why

does the Roman Liturgy commemorate martyrs

immediately after Christmas Day?

On the second, third, fourth, and fifth day of the Christmas Octave

(that is, eight consecutive days of Christmas mornings), the Roman Liturgy

commemorates the following martyrs: St

Stephen the Proto-Martyr (26 December), St John the Apostle and Evangelist (27

December), the Holy Innocents of Bethlehem (28 December), and St Thomas Becket

(29 December).

These feasts began to be placed in close proximity to Christmas as early

as the fourth century, when we know St Stephen was already commemorated the day

after Christmas. St Thomas Becket's feast is the most recent, having been

established in 1173. So why do we

commemorate these martyrs so soon after the merriment of Christmas morning? —for

the very simple reason that Christian merriment is given only to those who will

accept the costliness of following Jesus.

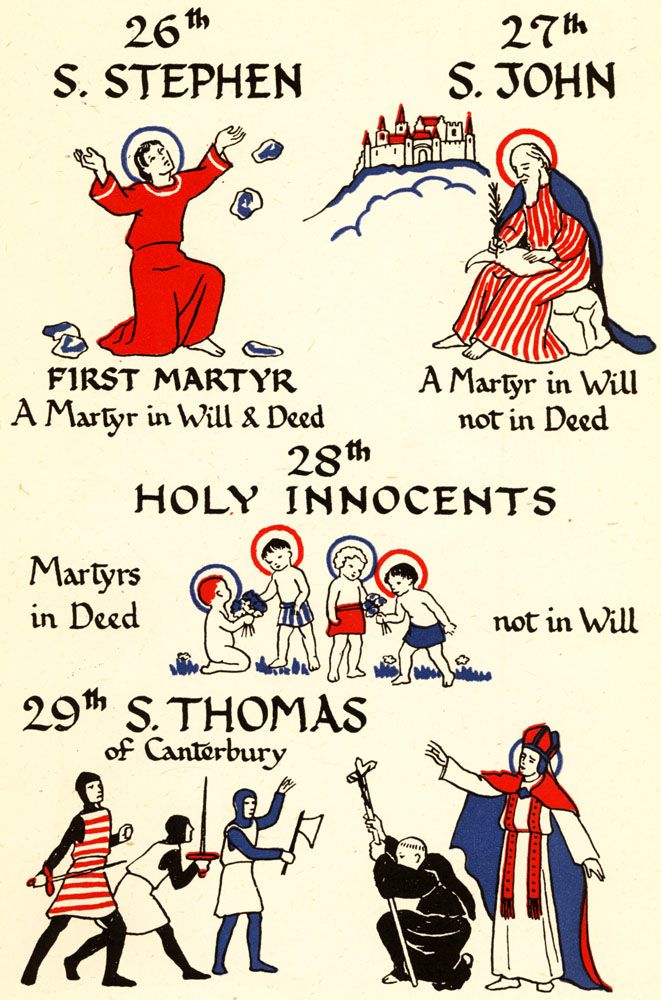

Each of these four martyrs represent four different ‘paradigms’ of

martyrdom. St Stephen the Deacon,

proclaimed Jesus and stirred the ire of an resistant audience and was stoned to

death (Acts 7:54-60). Thus St Stephen was a martyr in will and in deed.

St John the Apostle and Evangelist is the only Apostle who did not die

of martyrdom—though he was tortured by the Emperor Domitian reputedly by being

boiled in oil—but survived. Afterward,

he was exiled on Patmos “on account of the word of God and the testimony of

Jesus” (Apoc 1:9). Since St John was tortured for his faith in

Jesus, he is also technically called a confessor,

but it stands that he was a martyr in

will but not in deed.

The Holy Innocents of Bethlehem were slaughtered by wicked Herod the

Great in his paranoid attempt to retain his throne, as he was fearful that

Jesus—the long-foretold King of Israel—would usurp his rule. In attempt to eliminate the threat of the Christ

Child, Herod ordered all male children aged two and under to be killed, hoping

to kill baby Jesus as well (Mt 2:16-18). Thus, the Holy Innocents were martyrs in deed but not in will, since

they were too young to understand for Whom they were giving their lives.

With the Archbishop St Thomas Becket (also known as St Thomas of

Canterbury), the Primate of All England, we end the four martyrs’ commemoration

the same way we began: he was a martyr both in deed and in will, with

one slight variation: He died for the

liberty of Christ’s Church. Since the

Church is the “fullness of Christ” (Eph

1:23) and is, indeed, the Body of Christ Himself (Rom 12:5; cf Acts 9:4-5),

he is rightly recognized as a martyr for Jesus, even if in a roundabout way.

Again, we have a right to our merriment at the birth of Jesus only if we are willing to give to Him everything. St Paul wrote, “I appeal to you, therefore…by

the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual

worship” (Rom 12:1; see also Lk 9:62). Most of us, like St John, will suffer taunts

and ridicule on account of our following of Jesus, perhaps even to the point of

temporal loss; a few of us may even lose our lives, either for Christ as did St

Stephen, or for the sake of His Church, as did St Thomas Becket. And daily, thousands of children lose their

lives to abortion as did the Holy Innocents.

In a similar way, ISIS has killed hundreds of infant Christians since

seizing large swaths of Syria and Iraq.

Following Jesus is costly,

because He wants followers, not

fans. Are you a follower or just a

fan? Will you give to Jesus everything, He Who alone can give us eternal life?

Nota bene: On Wednesday, 28 December, Corpus Christi

Parish will present Becket, perhaps

the best film adaptation of St Thomas Becket's martyrdom. It will be worthwhile viewing since his circumstances

are not too different from our own today here in Canada. Also, our February convocation of the House of Ephesus will have for its topic

“The Grace of Martyrdom.”