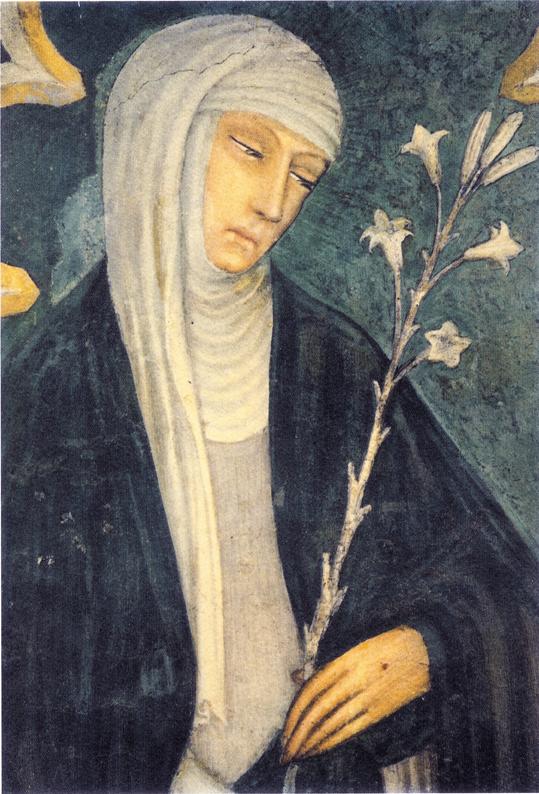

The following is a homily I preached in the presence of the Dominican community at Couvent St-Jean-Baptiste on the occasion of the Order's commemoration of St Catherine of Siena.

While at table for our Epiphany dinner in 2019, a few of us somehow struck up a conversation about today’s saint, and one of the friars admitted with his characteristic candour, “I do not like Catherine of Siena—she is just too crazy for me.” Anyone who’s read even a paragraph of her Dialogues knows exactly what he’s talking about, and probably secretly agrees that she’s a hard one to control.

The gospel’s image for the Holy Spirit, “Rivers of living water” which “will flow from within” (Jn 7:38) the Lord also gives the impression of something uncontrollable. In fact, all of the Biblical metaphors for the Holy Spirit seem to make the same point, whether it’s a bursting stream of water, a blazing fire, or a blustery wind. John the Baptist’s prophetic word about the Anointed One baptizing us with “fire” (Lk 3:16), this same Christ who “wished it were already kindled” (Lk 12:49) is nothing if not unsettling. Nicodemus was right to be perplexed about this unpredictable Wind making “everyone born of the Spirit” (Jn 3:8) equally unpredictable. And the fact that the elemental diversity of water, wind, and fire—besides the fact that they don’t mix very well—perhaps tells us something of the Holy Spirit’s recalcitrance. Small wonder the field of Pneumatology is so difficult. Thank God for Yves Congar!

What my former rector said about my seminary could very well be applied to Catherine, “It’s a crazy house, but that’s a good thing.” He was thinking of variety and excitement, except those were things Catherine did not like. The goodness of her craziness—if you’ll forgive my momentary irreverence—was located in her very surrender to “Love,” a favourite sobriquet for the Holy Spirit. As anyone who’s been in love knows, the only sensible thing to do is to surrender to it. I believe the expression is “crazy in love,” and Catherine certainly was. Here we’re talking about the Loving between the Lover and the Beloved; only, the world’s been caught in-between. This is the heart of the Church’s Mission: To tell the world to just “go with the flow”—pun intended.

A few years ago, a friend of mine said “Give the Holy Spirit sovereignty.” We’re now peregrinating towards Pentecost; if anything, our consistent reading from the Acts of the Apostles throughout Easter highlights the inescapable necessity of pairing the Gospel proclamation with the Holy Spirit’s sovereignty.

The tricky bit is learning how to distinguish ‘hype’ from ‘Holy Spirit’ and that, in part, is done by again distinguishing Biblical ‘freedom’ described by the Apostle, “where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom” (2 Cor 3:17)) from ‘freewheeling.’ This, I submit to you, is what ‘redeems’ the lady of the hour’s “craziness.”

St Thomas tells us that the Seven Gifts make us free and ever freer, and that was the secret to being Catherine: She gave the Holy Spirit sovereignty.

May her secret be ours, too.